Step back in time 110 years. You’re visiting London, England, in 1908, maybe for the first time. You want to know everything. Luckily you have a guidebook with you. Beyond the opening hours of the British Museum and the location of Sir Christopher Wren’s tombstone in St. Paul’s Cathedral, what is your guidebook telling you about London?

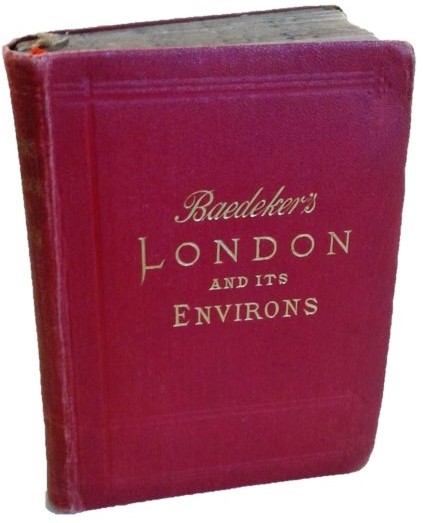

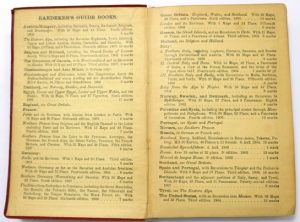

This post takes a critical look, in the form of an article, at how London is represented in a popular guidebook, Baedeker’s London and Its Environs of 1908. (It’s also an excuse to spend time examining my own personal copy, a prized possession, purchased from the wonderful Bryars & Bryars antiquarian map and book shop in Cecil Court, London.)

1. Introduction

Gilbert and Henderson observe that “From their inception, with the nineteenth-century handbooks of John Murray and Karl Baedeker, modern systematic guidebooks have been castigated as obvious, plagiarizing, formulaic, even cannibalistic….”1

For historians, however, guidebooks are rich primary sources, worthy of interest and study.

An analysis of the content of guidebooks to a particular place may be performed in a number of ways, such as horizontally, looking at a set of different publishers’ books from a single year, or vertically, looking at a series of the same brand of guidebook over time.

This article, however, will pursue a third method of analysis, by examining the content of one particular guidebook in depth, Baedeker’s London and Its Environs of 1908, which presents an especially deep mine of information about Edwardian London.

Such an approach is appropriate considering the volume and encyclopedic detail of information included in the text. Though obviously written for the contemporary visitor to London, this compact and iconic red book is now a bountiful source of insight into the status of the post-Victorian and pre-World War I city. This article will argue that Baedeker’s2 handbook represents London to the reader as a city of history, a city of modernity, and a city of division.

1.2 Background

Baedeker guides were published between 1832 and 1943 by the Leipzig, Germany, firm founded by Karl Baedeker (1801-1859).3 However, guidebooks have been in production since far earlier times.

Whitfield refers to an example from classical literature, Pausanias’ Guide to Greece, written from around 160 AD, in which “We learn that even at this date, places such as Corinth and Delphi were already haunted by professional guides, who preyed mercilessly on visitors, showing them the sites and telling them their history.”4

How might one define a guidebook, as distinct from other travel literature? The term is fluid but Gilbert notes that the modern guidebook, as a genre, was well-understood by the mid-nineteenth century as “a volume of advice for the tourist, usually including maps, illustrations, details of important sites, and often one or more itineraries connecting those sites.”5

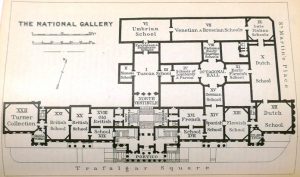

Vaughan adds that “In general, guides provide short descriptive inventories of the places, institutions and monuments likely to be of interest to their users in the judgement of the author, whose personal feelings may emerge by implication or by direct comment.”6 Vaughan’s use of the word “inventory” is quite appropriate for the 1908 Baedeker, as it includes a staggering amount of detail on sites judged of particular interest by the author, such as a delineation of every painting hung in the National Gallery, with full titles, locations, and selected interpretative comments. The guidebook thus, at times, also resembles and performs as a catalogue.

As a primary source, Baedekers in general are interesting due to their special place within the guidebook genre. As Parsons writes, “Not only did Baedeker’s guides reinforce the notion of canonic artefacts, they themselves became icons of canonicity…. Indeed, ‘Baedeker the brand’ received the ultimate in terms of recognition: it passed into the language, like Xerox, Hoover, Kleenex and, yes, the more plebeian ‘Cook’s Tour’.”7

As for its form, Baedeker guides were designed for convenient use, with their compact size and shape. The stiff binding and strong cover were meant to resist the wear and tear of use while travelling, which is indeed why many examples survive today. The bright red cover would promote brand recognition at the point of purchase, and also to other people observing the book’s use, thus serving as a marketing device. It is notable that a contemporary series of guides published by Ward Lock & Company also features red covers, which is reflective of the competition between the two brands.

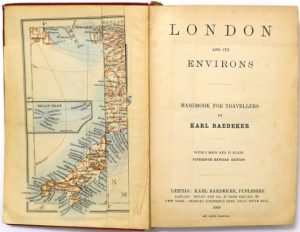

The main formal criticism of the 1908 Baedeker, from a modern perspective at least, is that in an effort to provide as much information as possible, the text fonts used are so small that reading may become difficult. The density of the text is also daunting, as the guidebook contains 600 pages with over 260,000 words, approximately the same length as James Joyce’s Ulysses! However this density does not seem to have discouraged the sales of the London guide, which was first published in 1878 and was in its fifteenth edition in 1908. It is notable that unlike other guides of the day, no illustrations (other than plans and maps) are included, and no advertising, the latter due to Baedeker’s firm-wide editorial policy.

In his extensive survey, London: The Biography, Ackroyd refers to a vogue for guidebooks to London beginning in the late seventeenth century, in both English and French.8 Such guidebooks were coincident with the development of detailed maps of the city following the Great Fire of 1666, such as Ogilby and Morgan’s published in 1676.

The popularity of Baedeker guides in general in the early twentieth century and contemporary attitudes toward their use are both exemplified in a novel published (conveniently) in the same year as our guidebook. E.M. Forster’s A Room With a View (1908) recounts the experiences of a young repressed English woman, Lucy Honeychurch, visiting Florence while chaperoned by her straight-laced cousin, Miss Bartlett. A new acquaintance, intrepid older English traveller Miss Lavish, is critical of Lucy’s over-reliance on information in her guidebook, saying, “Tut, tut! Miss Lucy! I hope we shall soon emancipate you from Baedeker. He does but touch the surface of things.”

Forster sets up a dichotomy between the “respectable” characters, like Lucy and Miss Bartlett, who rely entirely on their Baedekers for knowledge, and the more free-thinking ones, like Miss Lavish, who shun received wisdom (and in the end lead more rewarding lives). Evidently enough visitors thought Baedeker’s guide to London useful enough to keep the volume updated and in print until the last edition in 1930, by which time the requirements of travellers, and indeed the cultural geography of London, had changed.

1.2 Authorship

Initially the guides were a product of a single author, Karl Baedeker, founder of the “Baedeker dynasty,” as Parsons calls it.9 Webb refers to Karl Baedeker’s employing “full-time compilers to up-date the editions, and to retain the services of experts in fields such as art and architecture, for the specialist sections,” after successful sales of the 1880’s.10

However at the time of the 1908 London guide, editorship had passed to Karl’s son Fritz (1844-1925), and unsurprisingly “individual volumes were increasingly the product of a cooperative endeavour involving specialists in different fields and authors of different nationalities.”11

Gilbert notes that “The handbooks of Murray, Baedeker and their successors often chose to maintain a superficial pretence that they had been written by a single author, but were essentially corporate products, and increasingly were written to a specific formula.”12

Our 1908 Baedeker’s guide to London generally presents information from what sounds like a single author, but at points tellingly employs the pronoun “‘we”. Considering the great breadth and depth of information provided, such a team of authors, under one editor, was necessary if the guide was to be kept successfully updated.

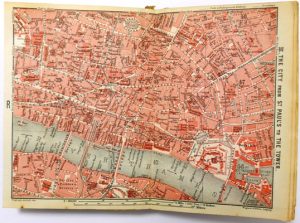

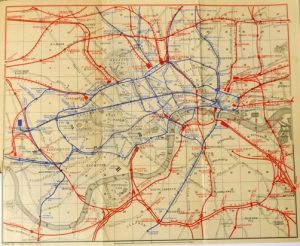

Our guidebook specifies that it has in fact been updated, right through mid-1908 (p. v). Many inclusions demonstrate this currency, such as that “Rotherhithe Tunnel, opened in 1908, is 1 ¾ M. in length (1535 ft. under the river) and 25 ft. in width; its cost is about 1,000,000l” (p. xxxii). Additionally, our guide reports the building of “the magnificent Roman Catholic Cathedral at Westminster” in 1903, of the War Office in 1907, and of the new Government Offices in June 1908 (p. xxvii). The maps, too, though undated individually, appear to show the latest information available about street plans and tube stops. The Kingsway and Aldwych development, for instance, opened by King Edward VII in late 1905, is clearly indicated.

1.3 Detail

Too much emphasis cannot be laid upon the high level of detail of information supplied in the guidebook, almost to the extent of trivia. For example, the guide provides statistics upon the following: the number of men in and annual cost of the fire brigade, the amount of water supplied to the city per person, the total yearly expenditure of Poor Law authorities, aggregate nightly audience at London’s theatres, music halls and assembly rooms, and the number of school age children in London aged 5-14.

Where the guide derives its information specifically is not stated. However, it may be that much comes from volumes listed in the “Books Relating to London” section, including the London County Council’s Survey of London and Whitaker’s Almanac (pp. xxxv-xxxvi). The guide also refers to the editor’s personal visits, and to “trusted” sources including “several English and American friends who are intimately acquainted with the great Metropolis” (p. v).

Such details make for rather tedious but fascinating reading now, with plenty of serendipitous insights into contemporary life for the historian. However, was this information useful to travellers?

Maybe so, as the figures included are not as random as they may seem. For example, the guide indicates that “At the census of 1896 [the City’s population] consisted of 4568 inhabited houses with 31,083 inhabitants (43,687 less than in 1871)” (p. xxx). Then it goes on to explain the relevance of this information, for the visitor’s understanding of the geography of London, saying, “The resident population is steadily decreasing on account of the constant emigration to the West End and suburbs, the ground and buildings being so valuable for commercial purposes as to preclude their use merely as dwellings” (p. xxx).

When the guide remarks that “On public holidays [Hampstead Heath] is generally visited by 25-50,000 Londoners and presents a characteristic scene of popular enjoyment” (p. 271), this gives the visitor a sense of the size of the population and the possible overcrowding of a popular (semi-)urban space – something potentially useful to know.

1.4 Audience

Thus the question arises: who was the audience for this publication?

This point may be examined from a number of angles. To begin, it is evident that the book was written for visitors, not residents, as indicated by the book’s subtitle, “Handbook for Travellers”. However, it is very likely that the book was read by London-dwellers and armchair travellers as well, for as Vaughan comments, “Many authors of guides and travel books knew that their work was for the entertainment and instruction of those who had no intention of deserting their own hearths.”13

Travellers would most likely have been British, American, or colonial citizens such as Canadians and Australians, or Europeans who could read English (although less likely French visitors, as they had their own French-language version of Baedeker’s London guide). Readers who travelled to London would likely be financially comfortable, in the middle to upper classes of the day, as the guide lists prices for moderate and luxury but rarely low-budget levels of service.

Much has been written on the distinction between traveller and tourist, and it is worth considering which of these is the intended audience for Baedeker’s guidebook. Boorstin writes that “The traveler, then, was working at something; the tourist was a pleasure-seeker. The traveler was active; he went strenuously in search of people, of adventure, or experience. The tourist is passive; he expects interesting things to happen to him. He goes ‘sight-seeing’… [and] expects everything to be done to him and for him.”14

It is clear from the above definition that Baedeker caters for the tourist. Never is the reader encouraged to take an active part in exploring the city. The visitor is only expected to read in great depth about the sights, and contemplate them in a rather intellectual and abstract fashion.

Kilbride argues that from the nineteenth century, with the commodification of travel, “Guidebooks not only told travelers what sights to see, at which restaurants to dine, and which hotels to sleep, but what to think about their experiences.”15 As previously noted, the stereotypical perception of Baedeker readers is that they will take information at face-value and receive the guidebook’s pre-digested opinions without exercising critical thought. Kilbride’s statement is overly prejudicial, however, since there must have been plenty of “Miss Lavishes” about who used the guidebook as a starting point for exploration, rather than a dictate of exactly what to see and how to think.

Baedeker’s London guide does indulge in the occasional editorial comment, such as in a tour of the National Gallery, in which the painting Dido Building Carthage “is not considered a favourable specimen of Turner, whose ‘eye for colour unaccountably fails him’ (Ruskin)” (p. 192).

However a close reading reveals that Baedeker’s 1908 guide is remarkably free of prescriptive advice or didactic instruction, contrary to prevailing popular belief. In fact, the guidebook’s chief objective, stated at the very beginning of the preface, is explicitly to “enable the traveller so to employ his time, his money, and his energy, that he may derive the greatest possible amount of pleasure and instruction from his visit…” (p. v).

Why might these readers of Baedeker’s guide have been coming to London at all? Whitfield identifies themes in travel literature, exposing motivations behind the act of visiting a new place, which include “exploration, conquest, pilgrimage, science, commerce, romanticism, adventure, imperialism, and so on.”16

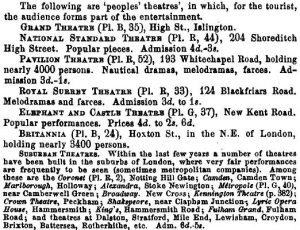

In the case of the 1908 travel guide, as noted, the motivation ascribed to visitors by the publisher is the derivation of “pleasure and instruction” (p. v). It is quite interesting in the guide how the two ends are woven together so closely as to be indistinguishable, as in a discussion of London theatre. Baedeker says that, “A visit to the whole of the theatres of London, which, however, could only be managed in the course of a prolonged sojourn, would give the traveller a capital insight into the social life of the people throughout all its gradations” (p. 44). Even more explicitly, Baedeker notes that “The following are ‘peoples’ theatres’, in which, for the tourist, the audience forms part of the entertainment,” including the Pavilion Theatre in Whitechapel, featuring “nautical dramas, melodramas, farces” (p. 47).

Are such visits meant to be pleasurable, instructive, or both?

2. City of History

Whether travellers find their visit to London pleasurable, instructive, or both, they will undeniably find they are in a city steeped in history.

In their own time, London visitors of 1908 were in an era of transformation during the (short) reign of King Edward VII (1901-1910), between Victorian values and the trauma of World War I. However, a prime attraction of the city was, and still is, its history, and manifestations of London’s past were to be seen everywhere.

Baedeker’s historical sketch of London begins with the detail that “At what period the Britons, one branch of the Celtic race, settled on this spot, there is no authentic evidence to shew [sic]” (p. xxiii). The publisher is to be commended for discretion in sticking to facts available at the time without speculative embellishment. After the brief sketch, the rest of the guidebook is packed full of historical information pertinent to individual sites as discussed. A sense of concern for accuracy and thoroughness pervades the guide.17

It is interesting to compare the historic sites considered unmissable in the “Disposition of Time” section of the 1908 guidebook (p. 82) with those of today. Baedeker gives the maximum two stars to St. Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey, and one star to the Tower of London, Hampton Court Palace, Kensington Palace and Temple Church. A review of modern guidebooks generally reveals that in 2018 the Tower of London has been promoted to a must-see, while the Temple Church has been demoted to simply of interest.

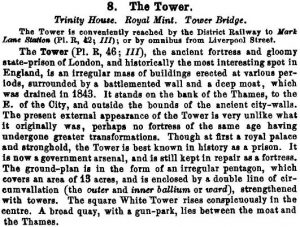

It is curious that Baedeker in fact refers to the Tower as “the ancient fortress and gloomy state-prison of London, and historically the most interesting spot in England” (p. 131), devoting nine pages (around 4,000 words) and a plan to describing its premises and contents, yet gives it only one star. Other than the above-noted descriptor “gloomy,” the publisher gives no affective account of the visitor experience to the Tower (beyond noting that “Free days should be avoided on account of the crowd” (p. 131)).

Perhaps Baedeker’s one star denotes that the Tower was less accessible (and lacking in onsite interpretation?) to tourists in 1908 than it is today, since the guide also notes that “visitors really interested” may obtain a special pass to see areas not shown to the general public, such as the dungeons below the White Tower, “gratuity to warder” (p. 133).

In addition to lists of must-see historic sites, Gilbert and Henderson remark upon a common feature of London guides, that “An imagined past was also woven into tourist geographies of the city by specific tours that sought out the London of literature”18 In accordance with this, Baedeker’s guide contains many references to historic literary locations worthy of notice, even some no longer existing, such as “The White Hart… in the Borough High Street, mentioned by Shakspeare [sic] in ‘Henry VI’. (Part II, iv. 8) and by Dickens in the ‘Pickwick Papers’… [which] was pulled down in 1889″ (p. 378).

Baedeker’s guide truly presents London as a city of omnipresent history, real and literary, down to the detailed location of Dickens’s grave in that most historic of locations, Westminster Abbey (p. 235).

2.1 City of Empire?

A review of the literature suggests that London as city and centre of empire was a common theme in guidebooks of the time. For instance, in his article “Exhibiting London: Empire and the City in Late Victorian Guidebooks,” Looker proposes that “Through a series of symbolic procedures, abetted by the texts of guidebooks, London became both object of and stage for an imperial pageant – a ‘dramaturgy of power’ – aimed largely at these visitors.”19 Furthermore,

It is true that contemporary guides, such as Ward Lock’s of 1907,21 are in effect textual representations of empire in this manner. However, such an interpretation proves highly problematic for Baedeker’s 1908 London guide. Why should this be so?

It is a central fact that Baedeker’s series of London guides was the product of a foreign publisher. First appearing in 1878, the guides were produced not from London, like Ward Lock’s, but from Leipzig, Germany. Indeed, the 1908 guide’s inside cover lists the geographical range of books available with all prices shown only in German currency (marks and pfennigs). This practice is rather curious, since the largest market for purchasers of the London guide was outside of Germany.

Nevertheless, it is sensible to propose that a German publisher would have little stake in producing a guidebook in explicit support of the British Empire. Baedeker’s mandate was quite simply as stated in the preface, to enable travellers to make the best use of their time, money and energy. Such an objective, coming from a German publisher, had little to do with any inclusion of imperial subtext which Looker and others22 have found in the domestically-published guides.

3. City of Modernity

Baedeker’s guide shows off 1908 London as a city of modernity in numerous ways throughout the book, referring often to the city’s size. “The name ‘London’,” the guide says, “is a word of indeterminate scope, and no official use of the name corresponds exactly to the huge continuous mass of streets and dwellings that now form the great and constantly extending Metropolis – a city which, in the words of Tacitus (Ann. 14, 33), is still ‘copia negotiatorum et commeaturum maxime celebre'” (p. xxviii).

The inclusion of a Latin passage, incidentally, may seem peculiar to modern readers, but is perhaps indicative of the educational standard of users of the day, who may have studied the language in school as a matter of course. In any case, Latin emphasis included, Baedeker’s point about the enormous size of London is well made.

London’s modernity is also manifested in its technological achievements, including the installation of gas-lighting one hundred years earlier, in 1807, such that “From that time to the present London has been actively engaged, by the laying out of spacious thoroughfares and the construction of handsome edifices, in making good its claim to be not only the largest, but also one of the finest cities in the world” (p. xxvii).

Baedeker devotes a great deal of attention to the new underground transportation, saying that “Within the last few years the ‘intramural’ traffic of London has been practically revolutionized by the development of the system of underground tube-railways, and London is now perhaps the best-equipped city in the world in respect of convenient, rapid, and cheap communication between the most important quarters” (p. 29).

The modern post office appears exceedingly well-organized if we are to believe that “The number of daily deliveries of letters in London varies from four to twelve according to the distance from the head office at St. Martin’s le Grand” (p. 40). Such efficiency may be due to the machinery in the large Telegraph Instrument Galleries (“admission by request from a banker or other well-known citizen”), which contain “500 instruments with their attendants. On the sunk-floor are four steam-engines of 50 horse-power each, by means of which messages are forwarded through pneumatic tubes to the other offices in the City and Strand districts” (p. 95).

Gilbert points out that “tourists from the early nineteenth century onwards also visited London to see a new world in the making.”23Following that century’s “march of improvement [which] was so rapid as to defy description” (p. xxvi), the guide takes an indifferent attitude to historical preservation in a way that may seem jarring to modern readers. On the ancient Roman wall, for instance, “This wall was maintained in parts until modern times, but has almost entirely disappeared before the alterations and improvements which taste and the necessities of trade have introduced” (p. xxiv). Note that “improvements” is not used in an ironic sense.

4. City of Division

Of course, all was not modernity and progress in early twentieth-century London. There remained a dark side, as had been described by Dickens in the latter half of the previous century. Writing about London as late as 1925, George Gissing remarks that “Passing from the shadow of the workhouse to that of criminal London, we submit to the effect which Dickens alone can produce; London as a place of squalid mystery and terror, of the grimly grotesque, of labyrinthine obscurity and lurid fascination, is Dickens’s own; he taught people a certain way of regarding the huge city, and to this day how common it is to see London with Dickens’s eyes.” Seeing London “with Dickens’s eyes” reveals that our 1908 guidebook still represents a city of division, by visitor or local, by male or female, and most startlingly by class.

4.1 Visitor or Local

Baedeker’s guidebook maintains a strict separation between the social and physical spheres of the visitor and the local. The general hints go so far as to recommend that “It is even prudent to avoid speaking to strangers in the street” (p. 77). For instance, a suggested “Preliminary Ramble’” in the city affords as little interaction with locals as possible, as it occurs not on foot but by omnibus! As Baedeker recommends,

Buzard very aptly points to the objectifying attitude inherently encouraged by our guide, writing how “Tourists abroad have seldom been prepared to consider how the foreigners among whom they move carry on any of those unspectacular commerces that have nothing to do with the visitor’s witnessing.”24

What the visitor does witness is seen with a “tourist gaze,” involving the visual collection of signs and their interpretation, upon which Urry has written extensively.25 Other than visits to peoples’ theatres noted above, where under the tourist gaze “the audience forms part of the entertainment” (p. 47), the guide includes very little about the day-to-day life of Londoners, by contrast a subject of overwhelming interest to guidebook readers today.

In Baedeker’s defence though, the silence of local residents may be attributable to the foreign nature of the publisher, for as critic George Jacques writes, “What, for instance, would a Frenchman or an Italian be able to say about the interior, or domestic life of America, after having seen little else than the outward, public life of streets and hotels?”26

4.2 Gender

The London of Baedeker’s 1908 guide is very much a gendered space, and many understood standards of formal behaviour for both sexes are inherent in the text. For instance, certain hotels are only appropriate “for single gentlemen” such as Cox’s at 55 Jermyn Street (p. 4). It may be that such establishments provide facilities of a lower standard than the guide’s publisher would recommend for women’s comfort, a concern for propriety which is in evidence elsewhere in the book.

For example, on the Atlantic crossing, “Ladies should not forget a thick veil” (p. xiv). This precaution is presumably to protect from the cold, although no such advice to given for the (hardier?) gentlemen. On the above mentioned “Preliminary Ramble” about London, a view from the outside of the omnibus is recommended, next to the driver, unless “If ladies are of the party, [then] an open Fly (see p. 19) is the most comfortable conveyance” (p. 78).

The deference shown to women (or “ladies”) in the guide permeates all aspects of a trip to London including eating, sleeping, transportation, and even theatre-going. Ladies interested in evening outings might have been relieved to read that “The entertainments offered by the Music Halls have certainly improved in tone during the last ten or fifteen years, and ladies may visit the better-class west end establishments without fear, though they should, of course, eschew the cheaper seats” (p. 47).

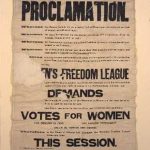

A particularly egregious (to modern eyes) example of London as gendered space occurs at the House of Commons, wherein “The Reporters’ Gallery is above the speaker, while above it again, behind an iron grating, is the Ladies’ Gallery” (p. 221). It was a trenchant sign of changes to come in British society that in October of that same year suffragettes would unfurl a Women’s Freedom League banner (now viewable at the Parliamentary Archives) from that gallery, and two women would padlock themselves to that very iron grating.

4.3 Class

Finally, London is presented as a city divided by class. Fashionable areas are pointed out containing mansions of the aristocracy, like St. James’s, Grosvenor and Berkeley Squares. Less salubrious areas are mentioned too, such as Bethnal Green and Leather Lane in Holborn, which is “largely inhabited by Italians of the poorer classes” (p. 99).

Indeed, Baedeker (probably sensibly) advises in the General Hints section that “Poor neighbourhoods should be avoided after nightfall” (p. 77).

Visitors are informed that “The usual dinner hour of the upper classes varies from 7 to 8 or even 9 p.m.” (p. 78), while “The Public Baths, which are plainly but comfortably fitted up, were instituted chiefly for the working classes, who can obtain cold baths here for as low a price as 1d., from which the charges rise to 6d. or 8d.” (p. 17).

For the visitor, a startling contrast might be that “Farther to the E. in Marylebone Road are the large buildings of Marylebone Workhouse…, nearly opposite the imposing premises of Madame Tussaud’s well-known waxwork exhibition…” (p. 284).

The guide is not unsympathetic to the reality of London’s poor, as it remarks that “About 20 per cent of the population live in overcrowded conditions, and much has been done, though much remains to do, to remedy this evil” (p. xxxii). In fact, the guide provides remarkable insight into social conditions of the time with its discussion of London’s charitable university settlements, albeit with an intellectual flavour, saying that “These residential colonies, which are intended to bring the knowledge and culture of the educated classes into direct contact with the needs and problems of the poor, for the benefit of both, are interesting to the student of social questions. The oldest and perhaps most characteristic example is Toynbee Hall (p. 144)” (p. 73).

Still there is a whiff of condescension in descriptions of tourist outings to Billingsgate, “the chief fish-market of London, the bad language used at which has become proverbial” (p. 124), and the London Docks, which feature “a large and motley crowd of labourers, to which numerous dusky visages and foreign costumes impart a curious and picturesque air” (p. 141).

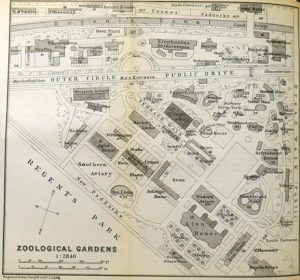

There is a sense of the guide’s promoting a visitor’s distant observation of the poorer areas of London in the same manner as it promotes a visit to the Zoological Gardens’ Llamas’ House, which “should not be approached too closely on account of the unpleasant expectorating propensities of its inmates” (p. 287).

5. Conclusion

As Weller succinctly observes, “An old Baedeker can serve as a good barometer for how much the world has changed,”27 and this certainly applies to the 1908 publication Baedeker’s London and Its Environs which is the subject of this article.

Far from frivolous, the guidebook’s contents reveal a vision of London presented to domestic and international travellers, as a city of omnipresent history, a city of modernity and progress, and yet a city divided into separate physical and social spheres. The guide unaccountably avoids any discussion whatsoever of the city’s weather (perhaps too banal to mention?). Nor is more than a passing mention made of the 1908 Franco-British Exhibition nor the 1908 Olympic Games, but this is not too surprising, since no other events of a temporary nature are detailed.

Much in Baedeker’s London may seem odd to modern readers, as that “On Sundays the [Metropolitan Line] train-service is suspended during the ‘church interval’ (11a.m.-1p.m.)” (p. xxxii), or that “Nine asylums are maintained [by the London County Council] at an annual cost of nearly 500,000l. for 17,000 lunatics” (p. xxxii).

However some of the guidebook’s practical London advice is rather timelessly sensible, as when “The stranger is cautioned against going to any unrecommended house near Leicester Square, as there are several houses of doubtful reputation in this locality” (p. 5). If Baedeker were to publish a 2018 guidebook to London, it might say the same.

Read the full text of Baedeker’s London and Its Environs (1908) free online at Internet Archive:

If you found this post interesting, feel free to share it.

- D. Gilbert and F. Henderson, “London and the tourist imagination,” in P.K. Gilbert ed., Imagined Londons (Albany, 2002), p. 122.

- Unless otherwise specified, the term “Baedeker” refers to the publisher / editor, the guidebook’s omniscient voice, not to Karl Baedeker, his sons or grandsons as authors.

- A. Weller, “Baedeker revisited,” Forbes, 27 September 1993, p. 188.

- P. Whitfield, Travel: A Literary History (Oxford, 2011), p. 11.

- D. Gilbert, “‘London in all its glory – or how to enjoy London’: guidebook representations of imperial London,” Journal of Historical Geography, 25(3) (1999), p. 282.

- J. Vaughan, The English Guide Book c. 1780-1870: An Illustrated History (Newton Abbot, 1974), p. 64.

- N.T. Parsons, Worth the Detour: A History of the Guidebook (Phoenix Mill, 2007), p. 198.

- P. Ackroyd, London: The Biography (London, 2001), p. 116.

- See Parsons, Worth the Detour, pp. 193-215.

- D. Webb, ‘For inns a hint, for routes a chart: the nineteenth-century London guidebook’, London Journal, 6(2) (1980), pp. 212.

- Parsons, Worth the Detour, p. 209.

- Gilbert, ‘“London in all its glory – or how to enjoy London”’, p. 282.

- Vaughan, The English Guide Book c. 1780-1870, p. 70.

- D. Kilbride, ‘Travel writing as evidence with special attention to nineteenth-century Anglo-America’, History Compass, 9(4) (2011), p. 341.

- Ibid., p. 344.

- Whitfield, Travel: A Literary History, p. viii.

- The rare dubious fact slips in, though, such as the remark in the chronology of English history that in 1172 “Robin Hood, the forest outlaw, flourishes” (p. xviii).

- Gilbert and Henderson, “London and the tourist imagination,” p. 125.

- B. Looker, Exhibiting Imperial London: Empire and the City in Late Victorian and Edwardian Guidebooks (London, 2002), p. 3.

- Ibid., p. 3.

- Referring to government buildings on Whitehall, the Ward Lock guide says, “By a paradox typically British, these buildings, from which a mighty Empire is actually governed, display none of the pomp of power, while the Horse Guards, now little more than a cavalry guard-house, is always in daytime sentinelled by gigantic guardsmen, whose appearance is calculated to excite awe and admiration in all beholders.” Ward Lock & Co. Limited, A Pictorial and Descriptive Guide to London and Its Environs (London, 1907), p. 89.

- See Gilbert, “‘London in all its glory – or how to enjoy London,'” pp. 279-297.

- Gilbert, ‘“London in all its glory – or how to enjoy London”’, p. 281.

- J. Buzard, “A continent of pictures: reflections on the ‘Europe’ of nineteenth-century tourists,” PMLA, 108(1) (1993), p. 31.

- See J. Urry, ‘The tourist gaze “revisited”’, American Behavioral Scientist, 36(2) (1992), pp. 172-186.

- Kilbride, ‘Travel writing as evidence with special attention to nineteenth-century Anglo-America’, p. 340.

- Weller, ‘Baedeker revisited’, p. 188.