Like many people, I love watching history on television. Bring on the Lucy Worsleys, the David Starkeys, the Tony Robinsons, Dan Snows, Michael Woods, Simon Schamas (especially the Simon Schamas), and the Horrible Histories too.

The medium does have its downsides, including potentially invoking the stereotypical Famous Historian in the 1975 film Monty Python and the Holy Grail (warning: gory).

Thinking critically, do the strengths of television history outweigh its weaknesses? As an excuse to rewatch and share some of my favourite shows, let’s consider this question.

By television history, I mean single or episodic programs originally aired on TV, dealing with historical events or evidence, with the goals of education and/or entertainment.

I’m going to argue that yes, the strengths of TV history DO outweigh its weaknesses … but strengths and weaknesses compared to what? It is BOOKS that are lurking in the background of this discussion. At the outset, therefore, let me remind us that books and television are two different animals, with two different natures. I am not going to suggest that TV history is superior to or meant to replace books; only that, like film, it has value on its own terms.

This discussion may be approached in a number of ways, but I’m going to focus on two areas of strength of history on television:

- One is content: what is presented.

- The other is form: how is it presented.

As examples, let’s look at some episodes from three modern TV history programs dealing with British history. I’ve chosen these shows since they all cover comparable ground, albeit in different ways, and I feel they’re all sound examples of the potential of TV history programs as a source of historical knowledge.

1. The first is Simon Schama’s A History of Britain, a 15-part BBC series, co-produced with the History Channel, which first aired in the UK in 2000. This is perhaps the best known example of the modern television history genre (Episode 1, 59 mins).

2. The second is an episode from the American History Channel documentary series Cities of the Underworld: London, City of Blood. This particular episode aired in 2007, and the series of 40 shows ran through 2009, exploring existing historical evidence under cities all over the world (Jerusalem, Tokyo, Prague, etc.). The host is Don Wildman, an American presenter who is not a historian (42 mins).

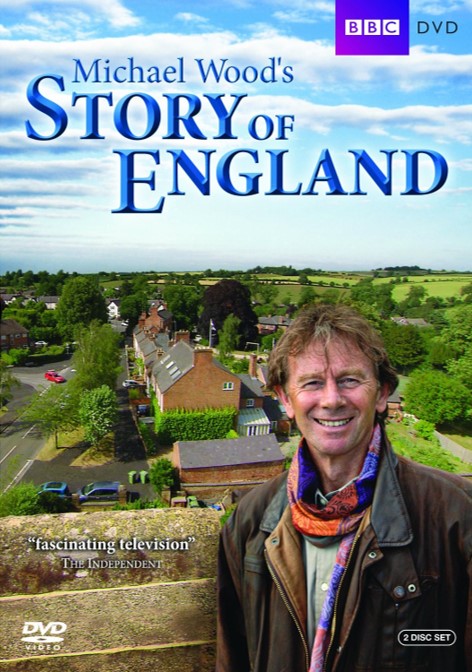

3. The final example is Michael Wood’s Story of England, made by Wood’s own production company, Maya Vision International, and distributed by the BBC. In this 2010 six-part series, Wood uses the history of one village (Kibworth, in Leicestershire) to exemplify events in the nation as a whole (Episode 1, 59 mins).

CONTENT

Choice of Content

Let’s begin by looking at choice of content. Consider that in his book Consuming History, Jerome de Groot notes that “Historians are suspicious of the superficiality of television, its inability to present complexity.” The viewing public is also critical. For example, shortly after the first airing of Schama’s program in the United States, the New York Times printed the following letter to the editor.

I would counter that Schama has explicitly chosen his narrative to present A history of Britain, not THE history of Britain. The program’s intent is to provide an overview of British history, over 15, not 150, one-hour episodes, and this naturally prohibits a deeply detailed account of events.

The material he has chosen to present shows a keen awareness of the nature of his audience, the general public, consumers of what the letter-writer rightly calls “popular history.” Far from dumbing-down, I would suggest that Schama’s program has eloquently summarized and made accessible a highly complex story.

References

One weakness of history on television is the lack of direct reference sources given for material presented, and for images and locations featured. For example, it’s frustrating to me when Schama shows footage from a plague pit recently excavated in London without mentioning where it’s located.

Ten years later, though, Michael Wood’s program does a much better job of indicating that he’s in the Leicester Archives, for instance, with unobtrusive onscreen captions. Television still does not provide the detail of footnotes or citations available in books or articles, which is a limitation of its nature.

Visual Content

The advantage of TV history’s nature, though, is in the visual aspect of its content.

British author and historian David Cannadine has written that “Most historians think in words, but for television and film, they must think primarily in pictures.” The best television history draws on highly visual material, including archival photographs and film, illuminated manuscripts, visits to historical sites, digital reconstructions, re-enactments, etc.

The best TV history doesn’t just TELL us about the horrors of the plague. It uses visual sources to SHOW us how quickly the Black Death spread across Europe in 1348 (as Wood does with animated maps), to SHOW us how brutally the symptoms affected people (as Schama does, rather gruesomely, with actors), and to SHOW us the extent of the piles of bones found underground in London (as Wildman does).

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then perhaps a moving picture, with thoughtfully crafted sound, is exponentially more valuable.

Let’s move on to form.

FORM

Perhaps more than content, the strength of television history as a visual medium lies in form, in how it is presented.

Narrative

Our consideration of the “showing” of visual content leads us to a great strength of television history: narrative or storytelling. British historian and broadcast journalist Tristram Hunt writes that “… the creation of coherent narratives is one of the lead virtues of television history …,” and Michael Wood is a master at this.

For instance, Wood takes us through his suspicion that the ruins of a Norman castle are buried in the village, and gives us the sense of participating as he examines primary source documents and conducts a geophysical survey. We feel a sense of satisfaction and perhaps even exhilaration in the conclusion that yes, there is a Norman castle! He has taken us through the historical research process, and it’s a story well told.

Presentation (Presenter)

A further formal strength of TV history is the presence of the presenter. History on TV with a narrator has generally been presented in two formats: either an omniscient narrator, or a host speaking directly to the viewer (as the Famous Historian in Monty Python and the Holy Grail).

The immediacy of a skillful presenter will convey the narrative to the viewer in a powerful manner. Schama behaves like the traditional Famous Historian, speaking directly to the viewer (which is not a criticism). On the other hand, Bell and Gray comment that “… Wood’s persona is presented as that of the explorer and adventurer ….” At the far end of the spectrum, Don Wildman has no pretensions to being an academic. His enthusiasm, it’s true, may sometimes seem over the top. However, as presenter in Cities of the Underworld, he serves as a proxy for the viewer, someone who has received special permission to go where we may not.

The immediacy of a skillful presenter will convey the narrative to the viewer in a powerful manner. Schama behaves like the traditional Famous Historian, speaking directly to the viewer (which is not a criticism). On the other hand, Bell and Gray comment that “… Wood’s persona is presented as that of the explorer and adventurer ….” At the far end of the spectrum, Don Wildman has no pretensions to being an academic. His enthusiasm, it’s true, may sometimes seem over the top. However, as presenter in Cities of the Underworld, he serves as a proxy for the viewer, someone who has received special permission to go where we may not.

Re-enactments

A final strength of how history may be presented on television is also an area for potential weakness, and that is re-enactments. As Simon Schama has very aptly stated, in reconstructions you must be aware of “the line between plausibility and giggles.” How then to present something visually when there is, for instance, no archival film from the Middle Ages?

Well, Michael Wood’s program does a very successful take on a re-enactment, by using an Anglo-Saxon folk village staffed with costumed villagers, to demonstrate spinning, weaving and cooking. Furthermore, shows like Cities of the Underworld do a stunning job with innovative digital reconstructions, such as a rather wonderful animation of the sewerizing of London’s rivers.

In conclusion, as Cannadine writes, “At its best, television can convey the immediacy of historic events with unrivalled and overpowering vividness …,” and for reasons of content and form which I have outlined, I hope you’ll agree that the strengths outweigh the weaknesses of television history. I’m going to keep watching it.

Sources:

Erin Bell and Ann Gray, “History on Television: Charisma, Narrative and Knowledge,” in Re-viewing Television History: Critical Issues in Television History, ed. Helen Wheatley (London: I.B. Tauris, 2008), 150.

David Cannadine, “Introduction, in History and the Media, ed. David Cannadine (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 4.

Jerome De Groot, Consuming History: Historians and Heritage in Contemporary Popular Culture (London: Routledge, 2016), 171.

Tristram Hunt, “How Does Television Enhance History?” in History and the Media, ed. David Cannadine (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 95.

Robert A. Rosenstone, “History in Images/History in Words: Reflections on the Possibility of Really Putting History onto Film,” The American Historical Review: Forum on Film and History 93, no. 5 (December 1988), 1174.

Simon Schama, “Television and the Trouble With History,” in History and the Media, ed. David Cannadine (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 30.

If you found this post interesting, feel free to share it.